In the 1920s, Le Corbusier devised a massive and utopian urban design theory: the Radiant City, which raised great ripples among the architectural academic world and had great impact on incalculably projects. Countless architects and planners were moved by his passionate words and great plan for the future. The Radiant city was like a wonderful mechanical toy. Furthermore, his conception, as an architectural work, had a dazzling clarity, simplicity and harmony. It was so orderly, so visible, so easy to understand. It said everything in a flash, like a good advertisement. This vision and its bold symbolism have been all but irresistible to planners, housers, designers, and to developers, lenders and mayors too. (Jacobs, J. 1961) He became the idol hailed by architects, and his ideas were spread all over the world to have many ramifications. The immense influence on the 20th century inspired many architects upon the urban design strategies. Although nothing was built directly under this radical concept, it has gradually been embodied in scores of projects, ranging from low-income public housing to office building projects. The debate of it continued in the whole twentieth-century, and it was criticized by many scholars as a dream utopia, especially its disrespect for history, culture, human scale, etc. But it is still worth to discuss under today’s views and have a look on how it emerged, and what can be learned on modern context.

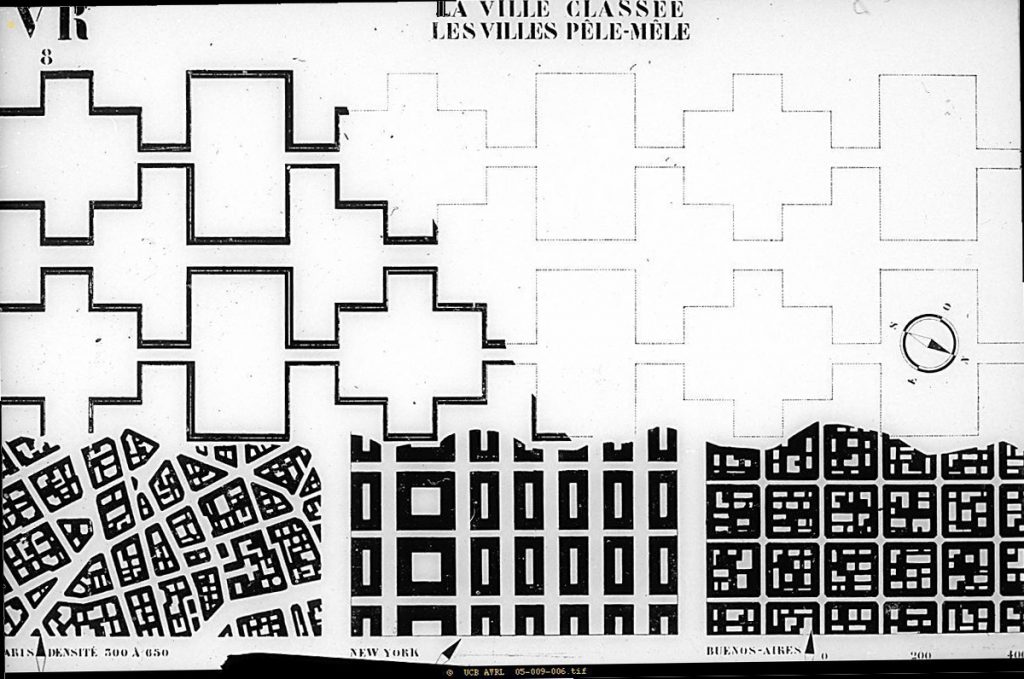

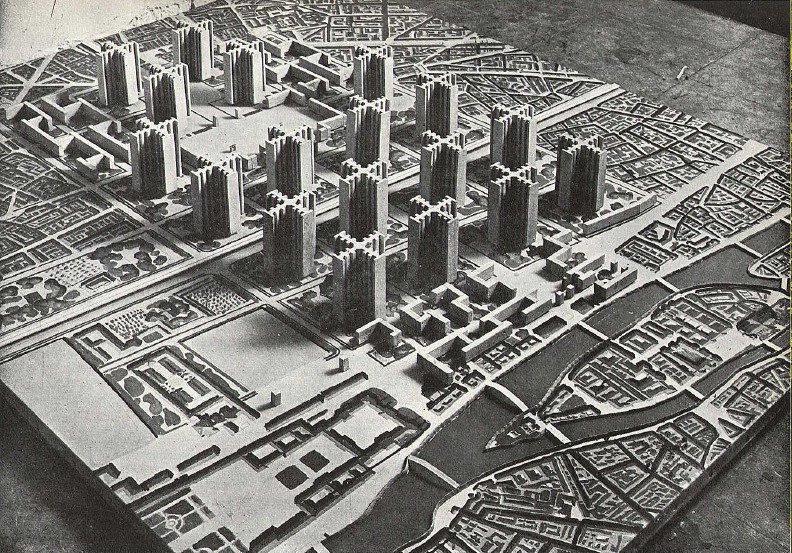

The Radiant City represented a utopian dream to reunite man within a well-ordered environment. Holding the slogan of “TO LIVE, TO BREATHE, TO HABITAT!”, he proposed completely replacing the traditional city form with a utopian technology based form. The city was to be built with high-rise buildings and was to be made accessible to fast modern transport. This allowed 99.5 to 100 percent of the ground space to remain open for maximum sunlight, fresh air, and green space. He appealed to improve the living condition of most poor people and build a new world with a “pyramid of natural hierarchies” on which order and planning could be based. Le Corbusier was planning not only a physical environment. He was planning for a social Utopia too. The keystone of the theory behind this city is the liberty of the individual. Its aim is to create respect for that liberty, to bring it to an authentic fruition, to destroy our present slavery. The restitution of every individual’s personal liberty. Waste will also have its throat cut. The cost of living will come down. The new city will break the shackles of poverty in which the old city has been keeping us chained. (Corbusier, L. 1930) The main characteristics as we can tell from the plan of Voisin in 1925 or the contemporary city of 3,000,000 inhabitants in 1922, he described the Radiant City is one uninterrupted park, the ground surface of the city is made up of parks, and no pedestrian ever meets an automobile; the automobiles are there of course, but in the air, passing by behind screens of foliage. (Corbusier, L. 1930) And the original idea was to create a city is entirely green, that is why the original name of it was Green City. Above the green land, erects many super blocks, which was criticized by Lewis Mumford as “buildings in a parking lot.” But the green spaces is the starting point and core idea that extended Le Corbusier’s a series of projects and ideas related to the Radiant City.

The born of the Radiant City was due to many reasons, only under such special historical backgrounds can Le Corbusier propose such a daring idea. It was destined to be the product of early twentieth-century, neither a bit earlier, nor a bit later. Following the influence of the Garden City movement and City Beautiful movement in the 1890s and 1900s, Jane Jacobs judged that Le Corbusier accepted the Garden City’s fundamental image, superficially at least, and worked to make it practical for high densities. He described his creation as the Garden City made attainable. The super-block and full of grass and lawns also indicates their similarity. We don’t know it is for coincidence or he created his ideas independently, but under the special circumstances in that historical stage, he must be more or less influenced by what one constantly sees and hears, and inherited some concepts from the Garden City movement and the City Beautiful movement.

Once in his book The city of to-morrow and its planning, he mentioned his worship for ancient Chinese cities for their great orderly plan. He compared the plan of Paris to Beijing, and said “Compare this plan with that of Paris, a little further on. And we Westerners felt called on to invade China in the cause of civilization.” That is one big reason he wanted to destroy the slum-like filthy old city blocks of Paris and create a new order.There are also latent political metaphors rooted in the Radiant City, which directly refer to his own political tendency in his planning inclination. During his professional career, he had sheered several times in political stand that lead to the transformation of his design concept. He used to believe in capitalism, then he turned to syndicalism and socialism, sometimes he worshiped fascism. He had intimate affiliations with many different political parties to struggle for the achievement of his planning concept. Just at an exhibition on Le Corbusier at the Pompidou Center 2015 commemorating the 50th anniversary of his death.

Three new books re-examined and pointed out this question. “Le Corbusier, a French Fascism,” by the journalist Xavier de Jarcy; “Le Corbusier, a Cold Vision of the World,” by the journalist Marc Perelman; and “A Corbusier,” by the architect and critic François Chaslin essentially argue that Le Corbusier’s aesthetics cannot be separated from his politics, which leaned more to the right than the left, despite work he did in Moscow. In their books, Mr. de Jarcy and Mr. Perelman argue that Le Corbusier’s architecture was inspired by Carrel’s unsavory ideas about how to clear out the old to make way for the new. Later, the architect proposed his Plan Voisin for Paris in the 1920s, in which he wanted to replace the urban blight of the Marais quarter with 18 glass towers on a rectangular grid with green space. Le Corbusier “projects his urbanism as a way to put forward his ideology,” Mr. de Jarcy said, “where the individual is destroyed by the group.” (Donadio, R. 2015)

The ideas of class society and collective living complex in the Radiant City are all catalyzed by his lost faith in capitalism, probably because in the middle of the Great Depression they had lost the capacity to fund him. Then he came to believe in the virtue of centralized planning, which would cover not merely city-building but every aspect of life. The way to achieve it would come through syndicalism, but not of the anarchist kind: this would be an ordered, hierarchical system, having some close affinities to the left-wing variety of Italian Fascism. Le Corbusier believed that syndicalism would provide a “pyramid of natural hierarchies” on which order and planning could be based. (Hall, P. 1988) Unlike the Paris of the 1920s, where rich and poor tended to live in close juxtaposition, the idea of the Radiant City would have been a completely class-segregated city that elite in the center, proletariat at the outskirts. At the centre were the skyscrapers of the Plan Voisin which, Corbusier emphasized, were intended as offices for the elite cadres: industrialists, scientists and artists (including, presumably, architects and planners)…., with 95 percent of the ground area left open. Outside this zone, the residential areas would be of two types: six-storey luxury apartments for these same cadres, designed on the so-called step-back principle (in rows) with 85 percent of ground space left open, and more modest accommodation for the workers, built around courtyards, on a uniform gridiron of streets, with 48 percent left open. (Corbusier, L. 1930) The living quality of segregated districts are distinguished by different percentage of green lands. The elite and middle-class possess the best core places, but the blue-collar workers and the clerks would not live like this. Le Corbusier provided for them in garden apartments within satellite units. But when he visited the United States in 1935, the freedom and equality concepts gave him deep impression and impact. The phalanstery also changed a bit in his mind. “If the city were to become a human city,” he proclaimed, “it would be a city without classes.” (Fishman, R. 1982)

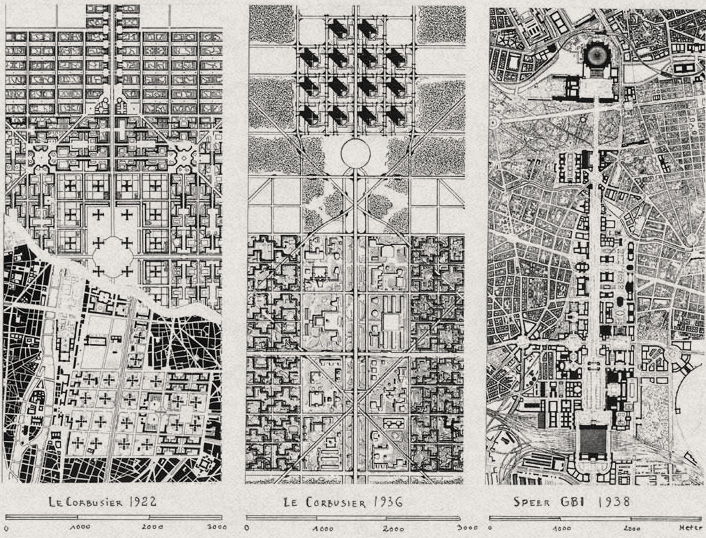

Le Corbusier had spent all his life improving and marketing the Radiant City. Every effort he struggled on is to make this dream utopia come true. But through a lifetime, nothing was ever built. He travelled all over Europe, and outside it, producing his grandiose urban visions with page after page of his book filled with the idea of the Radiant City, Algiers, Antwerp, Stockholm, Barcelona, Nemours in North Africa. All the efforts he made, were just remained on paper. To some extent, he was kind of pathetic in this respect. But the impact of the Radiant City at that time was enormous. Many architects inherited his unfulfilled wish and designed some big plans and building projects. In the planning of Cleveland, even like I.M.Pei, the internationally known architect and Erieview’s planner, argued that downtown development in a Radiant City style would “spread it rejuvenating influence—like ripples from a stone dropped in a pool—to neighboring blocks.” (Kolson, K. 2001) In the Third Reich, Hitler also appointed the chief architect Albert Speer to plan a new Berlin. As mentioned before, the fascism planning methods worked with Le Corbusier in a really close way. Speer made the plan to reconstruct Berlin on a grand scale, with huge buildings, wide boulevards, and a reorganized transportation system. A plan for monumental and eternity. When compare the plan produced on 1938 to the Radiant City, we can find many similarities, such as the ponderously inserted new architectures, the divine axis, and the gigantic super blocks. This plan also died in the vine for its huge budget and unrealistic imagination. Actually, most of these tries have failed, such as the Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Missouri in the 1950s. Designed by Minoru Yamazaki, he claimed that this project used the planning principles of Le Corbusier, residents were raised up to 11 floors above ground in an attempt to save the grounds and ground floor space for communal activity. Many new residents were attracted by their advertised idea of “an oasis in the desert”. But then “the best high apartment” decayed in an unbelievable speed, the complex had become internationally infamous for its poverty, crime, and segregation. Finally, the federal Department of Housing decided to demolish Pruitt-Igoe with explosives, and it became an icon of public-policy planning failure, to some extent, the failure of Corbusian planning theory.

Besides the projects consciously inspired by the Radiant City, the urbanisation and construction activities in the communist countries also inadvertently emerged some similar projects. Because of the similarity and implicit affinities between socialism and Le Corbusier’s concept, the monotonous row apartments are popular in these countries. Especially the large-scale demolition and reconstruction, the disrespect for history and local context, they both advocate the idea of abandon the old and embrace the new. To fulfill the physical needs without concerns to the people doomed their unanimated conditions. After half a century’s practices, facts have proved that these big plans are neither good for city nor for individual living. The Radiant City as the founder of these projects, has always been the focus for criticise and further discussion. The most influential one should be Jane Jacobs, who stood at the point of non-professionals, fustigated the ignorance of these irresponsible architects whom only want to fulfill their selfish planning ambitions but neglect the real needs of residents. Especially Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, which is a component of the ironic term “Radiant Garden City Beautiful”. She commented that it is like skyscrapers within a park. No matter how vulgarized or clumsy the design, how dreary and useless the open space, how dull the close-up view, an imitation of Le Corbusier shouts “Look what I made!” Like a great, visible ego it tells of some achievement. But as to how the city works, it tells, like the Garden City, nothing but lies. (Jacobs, J. 1961)

Although the Radiant City have raised controversies, but it also proved that it is a compelling theory which worth for discussions, even till today. Its inspirations and enlightenments directly facilitated the development of planning theories and construction practices in the twentieth-century. Learning from Le Corbusier, we could say that a good design not only comes from Utilitas, Firmitas or Venustas, it should also consider more wide aspects in social, economic, military, even political sides. The utopia he provided has been the most profound one since its birth that intangibly affected our daily lives. In spite of the unrealistic imaginations and exaggerated rhetoric, what I feel from it is the responsible and generous heart from an ambitious architect to improve the living conditions of all humankind. No matter its advantages or disadvantages, the Radiant City could be either an inspiration, or an alarm bell for the later generations.

References

Brott, S. (2013). Le Corbusier and the Fascist Revolution. Thresholds 41. MIT Press

Choay, F. (1997 [1980]). The rule and the model : on the theory of architecture and urbanism (D. Bratton, Trans.). Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Cohen, P. (1989). Architektur des Untergangs [motion picture]. New York / Toronto: First Run Icarus Films / Libra Films.

Corbusier, L. (1930). Radiant City. Art, Architecture and Engineering Library.

Corbusier, L. (1947). The city of to-morrow and its planning. Architectural Press.

Corbusier, L. (1931). Towards a new architecture. Courier Corporation.

Fishman, R. (1982). Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century: Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier. MIT Press.

Hall, P. (1988). Cities of tomorrow. Blackwell Publishers.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Vintage.

Kolson, K. (2001). Big plans: the allure and folly of urban design. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Panerai, P., Castex, J., Depaule, J.-C., & Samuels, I. (2004). Urban forms: the death and life of the urban block. London: Architectural Press.