Find full page on Escholarship:

https://www.escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/papers/5712m679j?locale=en

Abstract

Due to rapid urbanisation and construction in recent decades, Chinese cities have undergone great changes and overcome many conflicts. As the capital of China, the Old City of Beijing faced the severest challenges during this process. Without proper maintenance and management, the traditional courtyard houses have been dilapidated and living conditions in the city have been lowered drastically. Since 2011, a series of policies and strategies have been implemented in Dashilar, with the aim to preserve and renew the historic neighbourhood. Local residents were resettled to other areas to reduce an overwhelming population density. Various renovation projects have emerged to conserve and reuse the emptied courtyard houses. These projects were widely reported to have led to effective outcomes, and the author consequently decided to conduct a study on Dashilar.

The aim of this study is to record the local residents’ living conditions, to uncover the underlying causes of existing living problems, and to summarise lessons and experiences from the renovation projects. This study examines the influences of the renewal practices in Dashilar through a field trip to observe the revitalization activities and to collect essential information on the views of the local residents, project organisers, architects, and third-party professionals. This report presents field results that disclose the real living status of the local residents in Dashilar, and the entanglement of interests and motives among various stakeholders A complicated prospect now faces the ancient neighbourhood.

Résumé

L’urbanisation rapide et les travaux de chantier au cours des décennies récentes ont causé de grands changements, ainsi que plusieurs conflits dans les villes chinoises. Étant la ville capitale de la Chine, Vieux Beijing a fait face aux défis les plus difficiles durant le processus d’urbanisation. Sans entretien et gestion, l’état physique des maisons à cour traditionnelles et les conditions de vie dans la vieille ville se sont considérablement détériorés. Depuis 2011, plusieurs stratégies de renouvellement urbaine ont été implementés dans le quartier historique de Dashilar. Certains résidents locaux furent déplacés afin de réduire la densité de population. Des projets de rénovation variés, préservant et réutilisant les maisons à cour traditionnelles, furent complétés, et ces projets ont produit des opinions majoritairement positives. L’auteur a donc décidé de mener une étude sur Dashilar.

Cette étude a comme objectif de comprendre les conditions de vie des citoyens, de découvrir les causes premières des problèmes existantes, et d’analyser les projets de rénovation afin d’en tirer des leçons. Une enquête de terrain a été menée afin d’observer les conséquences des activités de revitalisation, et d’apprendre quelles sont les critiques des citoyens, organisateurs de projet, architectes et tierces personnes ou organisations. Dans cette dissertation, les résultats de recherche sont présentés, révélant les conditions de vie réelles à Dashilar et les motifs et intérêts des parties prenantes. Le quartier historique de Dashilar fait maintenant face à une prospective d’avenir complexe.

Acknowledgement

My sincere gratitude to Professor Robert Mellin, for his patient guidance and inspiring encouragement along with the development of this project. I am also grateful to Professor Ipek Tureli, whose critics and kind instructions helped me to initiate the study. I really appreciate Mr. Clifford C.F. Wong and School of Architecture of McGill for the generous fellowship that made this chance available.

Special acknowledgement to Joe Carter, who shared many valuable advices with my study. I am indebted to Xiujiao Song and Chuanhui Huang, who provided genuine helps during the field trip. Thanks are due to the worthy views from Haiyu Wang, Yong Jia, People’s Architecture Office, Dashilar Investment Ltd, and the local residents in Dashilar.

I also appreciate Marcia King, who is always generous in giving me her assistance and support. I would like to extend my gratitude to Alana Morgan Matheson, Zoey Cai and Lisa Chow, who spent precious time doing proofreading for my paper.

Finally, I would like to thank my parents and all my friends who supported me to finish this study with unconditional love and encouragements.

Chapter One: Introduction

1.1 Introduction

2.1 Literature Review on Past Experiences in China

Chapter Two: Old Cities of Beijing and Dashilar

2.1 Historic Urban Fabric of Beijing

2.1.1 Historic Beijing

2.1.2 Hutongs

2.1.3 Courtyard Houses

2.2 Historic Pattern of Dashilar Area

Chapter Three: Current Living conditions in Dashilar

3.1 Current Living conditions

3.1.1 Overcrowding Living Conditions.

3.1.2 Complex Housing Wwnerships.

3.1.3 Dilapidation and Illegal Extensions.

3.1.4 Lack of Adequate Municipal and Sanitary Facilities.

3.1.5 Insufficient Spaces for Daily Life.

3.1.6 Lack of Green Spaces.

3.1.7 Fire Dangers.

3.1.8 Sense of Public Security is Weak.

3.2 Historical Causes of Current Problems

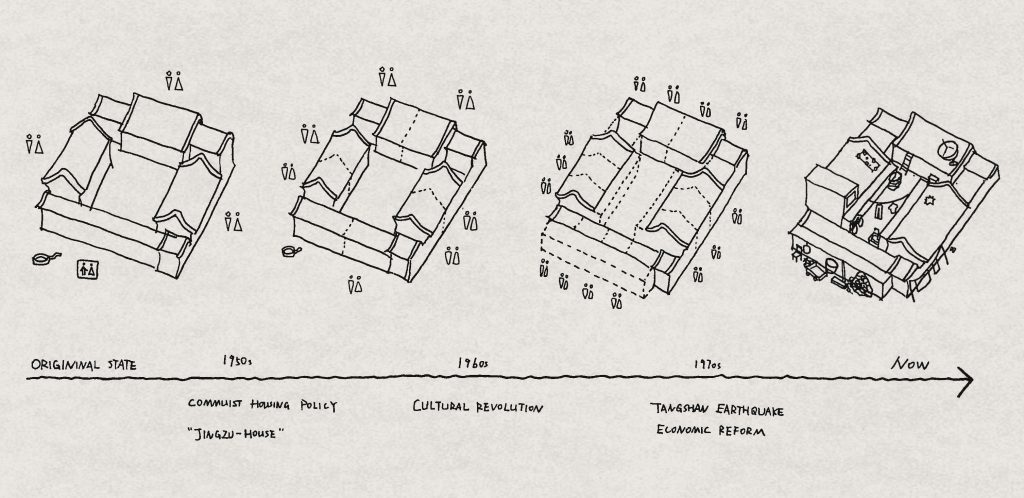

3.2.1 1950s and Liang-Chen Proposal

3.2.2 1960s and Cultural Revolution

3.2.3 1970s, Tangshan Earthquakes and Economic Reform until Now

Chapter Four: Conservation Strategies in Dashilar

4.1 Population Redistribution Policy

4.2 Dashilar Pilot Projects: Courtyard House Plugin and Others

4.3 Regular Renovations

4.3.1 Reconstructions

4.3.2 Reinforcements

4.3.3 Face-liftings

4.4 Private Renovations

4.5 Additional Ca

Introduction

The Problem

As an ancient country with a history of more than 5000 years, China has stepped into modernization rapidly and painfully since 1949, along with dramatic changes throughout the whole nation. The capital, Beijing, at the same time as a historic city, had faced the severest challenges during this process. In order to catch up with the developed world, the ambitious early industrialization schemes had reformed the cities with factories everywhere and neglected the traditional urban fabrics. Although the schemes were against Liang Sicheng and Chen Zhanxiang’s celebrated 1949 plan of Beijing, the industrialization had proceeded fast in the center of the capital due to Maoist urban priorities and policies. The renowned courtyard house – the siheyuan as the most notable vernacular housing type in China, and the basic, microcosmic unit of old Beijing’s entire layout, was argued by some experts in 1950s that it was obsolete because it could not adequately house multiple families. Many “backward” old city blocks had to be replaced by the “advanced” industrial somkestacks and high-rise apartments. Since then, the traditional landscape of historic old city of Beijing was challenged by the monotonous apartments and fell into crisis.

In fact, until the economic reform in 1978, the traditional urban fabrics have really begun to disappear at a high speed, influenced by the new development slogan that aims to gain as much as economic benefits by any means. With the flowing of new immigrants into Beijing, the pressure of population has catalyzed the redevelopment of old city blocks. The serious longstanding shortage of housing aggravated the conflict between the demand for new housing construction and the preservation of traditional neighbourhoods. The housing reform movements and government policies also supported the idea of Soviet-style collective high-rise communities to fulfill the need of rapid urbanization, which highly compressedthe spaces of courtyard houses. Moreover, the existing old courtyard houses began to dilapidate into severe conditions. The overcrowding population, deteriorating housing, threat from structural failure, frequent flooding, roof leakage, poor ventilation, and lack of infrastructure have resulted in substandard living conditions for most residents. Most of the courtyard houses have degenerated from spacious dwellings for single extended families to crowded multi-family compounds, the average living space is less than 8m2/person in these areas. The courtyard houses, which once had been the sanctuary of family life, had been deformed into unsightly shelters shared by several households. Some even crumbled, while others were replaced by apartment blocks. (Wu, 1999) At the meantime, the local residents also suffered from the constant lack of privacy in overcrowded living spaces that triggered a series of neighbourhood crises.

Before the recognition of the value of these historic old city areas, for the central government, the dilapidated structures are an embarrassment, leading to the razing of large expanses of courtyard compounds even in some of the most historic parts of cities. (Chow, R. Y. 2015) According to an analysis of aerial photographs published in 1989, there were only 805 relatively large and classically laid-out courtyard houses remaining in the Old City, occupying only 115 hectares, or about 1.9 percent of the Old City’s total land area of 6,200 hectares. (Jia & Liang, 1989) It is impossible that the remaining courtyard houses could Perpetuate forever due to its materials. So that the preservation and renewal of traditional courtyard houses have become extremely urgent for the municipal government and local residents. This problem has drawn wide attentions internationally, to some extent, the fate of the siheyuan in many ways reflects the challenges that face the preservation of architectural heritage throughout the developing world. (Bromley & Jones, 1995)

Fig. Illegal outbuildings occupying the courtyard spaces. (Retrieved from www.doczj.com)

Previous Preservation and Renewal Practices

With the growth of the comprehensive economic and political strength, the value of traditional urban fabrics as cultural heritage has been recognized by the government and local residents gradually. According to Beijing Municipal Institute of City Planning and Design, the earliest monuments designated for preservation by the post-1949 regime appeared in the law in 1957. But, courtyard houses, as such, were not designated for preservation until 1984, one year after the State Council proclaimed Beijing a “Renowned Historic and Cultural City.” Since then the typology of the courtyard house has been recognized as a specific system that characterizes the urban fabric of most historic cities of China. At this time all courtyard houses listed among the city’s preservation sites were designated at the municipal level, as opposed to the higher national level or the lower district level. In 1985 height limits were imposed on new construction in the Old City, and in 1987 these were further refined to include special “construction control zones” around designated monuments. (Abramson, 2001) Although the Master Plan of Beijing designates some quarters as “courtyard house conservation areas” (such as the Nan Luogu Xiang block in which Ju’er Hutong is located), their total floor space takes up a mere 300,000 square metres out of a total of 10 million square metres of old courtyard houses throughout the Old City. And the traditional housing outside the designated areas seems to have been totally abandoned to potential demolition. (Wu, 1999) Moreover, by that time, the theories and experiences of urban renewal in Chinese cities are almost non-existent, even those experts who advocated protection could not produce any practical solutions.

In 1987, Beijing launched a practical experiment that was inevitable and came out the most influential project– the Ju’er Hutong Project, which was one of four initial experimental projects in rehabilitating the derelict houses in the old city. It was implemented at Number 41 Ju’er Hutong, where the dwellings were in especially bad condition. Finally, it was honoured with six highest domestic awards and several international awards, including the Architectural Creation Award (representing the highest level of architectural design in China), ARCASIA 1992 Gold Medal Award for Architectural Excellence and the 1992 World Habitat Award. (Wu, 1999)

It was undeniably a ground-breaking milestone in the history of old city renewal in China. WU Liangyong proposed the idea of “organic renewal” – the approach seeks to establish a new organic order based on adaptation rather than on complete replacement. The courtyard houses in the designated area were sorted out into five types according to their physical conditions, and different strategies were adopted to different types, then this highly complex problem could be broken down into simpler parts. This project was highly praised by many architects and researchers in academia, and it surely improved the living conditions of the local residents. But such mode was not continued by the government and other developers due to its high cost of money and time. The prosperous real estate market in the 1990s also made the prices of courtyard houses rise dramatically which made such projects difficult to repeat. In addition, a series of post-renewal problems also emerged in the later years that indicate its disadvantages. Its high reputation brought the housing price to be among one of the highest in Beijing, thus leading to the selling and replacement of the local residents, and the intended open spaces were also enclosed to be private spaces. The original intention to provide economical housing actually failed.

Fig. Aerial view of Ju’er Hutong project. (Wu, L, 1999)

Since then the urban renewal practices were growing vigorously, although many only stayed on policies and didn’t achieve cultural and aesthetic value. The Three Old Reform movement that aims at abandoned urban industrial sites, dilapidated urban residential areas, and existing urban villages were developed through the country. Besides the experimental projects supported by the municipal government, many market-driven renewal projects also sprung up, most of them were tourist oriented, but some also geared to luxury housing. This process was driven by diverse motivations of different levels of the government, including transforming urban land use functions, demonstrating the entrepreneurial capability of local government, and maximizing negotiated land benefits. As China opened up its land and real estate development market, private and foreign investment aggressively entered the field of urban regeneration to seek maximum profit. (Ye, L. 2011) Usually these private projects were very expensive, and have the same problems as Ju’er Hutong. In order to compensate for the low building density required by preservation district regulations, the prices for these new “old-style” houses are extremely high — in the order of US$3,000–4,000 per square meter. Critics of the individual luxury siheyuan have identified a number of problems. These houses are often not the primary residence of their wealthy owners, and thus bringing gentrification and absenteeism to the neighborhood. Being owned by the wealthy, they also bring an increased level of car traffic into the narrow hutong and seclusion as the owners often prefer to close the galleries and verandahs. (Abramson, 2001) And such projects normally even reduced the number of families could be accommodated; they are more like a high-income elite resort rather than an affordable housing for local residents.

Above all, more than 20 years from the first phase of old city renewal practices, I think it is high time to assess the previous projects in today’s context. The advantages of the former practices are that they rescued a lot of historic sites, and greatly improved the original living conditions. Although these strategies reconstructed new courtyard houses, they did not rehabilitate the courtyard houses that were in severe conditions. The replacement of residents to a large extent affected the original neighbourhood compositions, which led to the destruction of traditional neighbourhood relationships. And for the original residents, who could not afford the high cost of living, were forced to sell their houses at a high price and moved to high-rise apartments. However, these practices have provided abundant experiences and theory bases for later projects. I believe this is a long-term process, in which we cannot be anxious to seek quick success and instant benefits. Soft fire makes sweet malt.

Contemporary Renewal Practices in Dashilar

Since 2011, a series of renewal policies and various renewal practices have been released to Dashilar area. More and more contemporary courtyard house renewal projects by ambitious young architects and artists have emerged in the old city of Beijing. Yangmeizhu Xiejie of Dashilar area was selected as the pilot place for such renewal practices and policies. Most of the projects have used different design languages than the former projects,representing the new era of old city renewals. Several remarkable avant-garde projects gathered in Dashilar area, such as the Courtyard House Plugin project and Humble Hostel project with their special design methods which have drawn my attention.

For 600 years, Dashilar has been one of Beijing’s most prosperous, and bustling cultural neighbourhoods. As stated within the city of Beijing’s Master Plan, Dashilar is officially recognized as one of 25 protected cultural and historic districts in the Old City of Beijing. The preservation, renovation and rejuvenation of Dashilar also face numerous difficulties just like other old areas. In 2011, Dashilar Project was launched by Beijing Dashilar Investment limited as an alternative redevelopment strategy for Dashilar. According to the website of Dashilar, this project is an open platform where parties and stakeholders can collaborate on exploring new methodologies in reaching this goal of a truly indigenous, sustainable and vibrant old city centre.

Fig. Map of Dashilar pilot projects. (Dashilar, org)

Besides the pilot projects held by the Dashiar Investment Company, at the same time, many regular renovations led by the local housing bureau are in process that provide a sharp comparison with the pilot projects. These regular renovations used a totally different way of renovation with traditional craftsmanship and techniques, at absolutely no costs for the local residents. The welfare-driven model with its special characteristics and implementation methods actually have more effective and wide-range effects on local residents’ lives. What’s more, private renovations by the house owners also exist, which are more exquisite and careful, and focus more on protection. Diverse types of renovations happening in one specific area provide a rare opportunity to have a look at the strategies they used and give a comprehensive assessment. In addition, some renewal policies such as the population redistribution set by the government are being carried out since 2011 as the fundamentals of the renewal of whole Dashilar area, which are valued to be discussed that act as the premises of all the renewal practices.

As they are the newest projects that have been done recently, the related research is very necessary to trace their design and construction process and to evaluate the post-renewal influences. With a critical comparison to the old renewal projects, I will provide a comprehensive review for future practices and propagate this excellent mode.

Goals and objectives of the study

Find answers of the questions:

What are the current living conditions in the traditional courtyard houses?

Did the renewal practices in Dashilar area improve the housing condition?

Today, the process of urban renewal is proceeding at an accelerating pace in the Old City of Beijing. Although a considerable number of courtyard houses have been destroyed, we scrupulously adhere to the creed that it is “never too late” for preservation. (Wu, 1999)

The main goal of this research is to provide documentary and critical reviews on contemporary renewal practices that can contribute to the future urban renewal directions. Following this, the research aims to find answers of such six questions. How to improve the living conditions of the old city blocks in China? What are the current conditions of the old courtyard houses? What are the local residents’ desires for a better living condition? How have the urban renewal projects promoted their living conditions? What are the differences between the old renewal projects and the new ones? What are the feedbacks, influences and future expectations of these renewal projects? By doing this research, I hope to get comprehensive reviews on these questions and help future practitioners finding proper way into the urban renewal practices in China and other developing countries.

Methodology

This research is both a quantitative and qualitative study based on observation and interpretation of particular projects. Various methodologies were used in the research field trip that include observations, photography, and interviews. All these methods were to provide collective information regarding the conditions of these courtyard houses and contribute to the critical evaluations of the renewal practices. The field trip was conducted for a month in May in Beijing. The books published by the designers and Dashilar Company, papers written by architectural commentators and previous related thesis works will be the main secondary sources.

This research has two main research objectives: cultural landscape and conservation strategies. The research areas were different in the two studies that the cultural landscape study was conducted in the whole Dashilar area to show a general landscape view, and the conservation strategies study was designated in several specific hutongs along Yangmeizhu Xiejie, where concentrated renewal projects and pilot population redistribution policy were located. The cultural landscape study in this area specifically focused on the distinct disorganized living environment of hutongs and courtyard houses which posed the urgent necessity to improve their living conditions. I will start with the uniqueness of Dashiar area that contains typological studies of history, urban context, street layout, hutong pattern, and courtyard houses, etc. During the field trip, following aspects of living conditions were specially recorded to provide a direct comparison with the post-renewal conditions:

Overcrowding living conditions.

Complex housing ownerships.

Dilapidation and illegal extensions.

Lack of adequate municipal and sanitary facilities.

Insufficient spaces for daily life.

Lack of green spaces.

Fire dangers.

Sense of public security is weak.

Along with the living conditions, some other observations of hutong’s daily life, food, street arts, shops, and tourism would be complementary cultural landscape to give readers a comprehensive understanding of Dashilar area. Except for direct observations and photographs, in-depth interviews showed an effective way for data collection. By randomly visiting and interviewing the local residents, an oral history of the dilapidation process and problems of daily life was clearly described. The local residents were eager to express their concerns about their living conditions. With experiences from the investigation questionnaire of Ju’er Hutong Project, I drafted the interview questions about their number of households, time span of residence, ownership of properties, average living areas, rent prices, infrastructure conditions, renovation desires, and current complaints etc. With summaries of the data collected, I will analyse how the living conditions of courtyard houses have turned from roomy, tidy to crowded and messy. Through comparison of the conditions now with the past, we will know what the local residents have suffered in recent decades. The analysis will explain why renewal was necessary and urgent, which would come up in the next part of conservation.

There were three types of conservation models: pilot renovation projects designed by famous architects and invested by the Dashilar Company, general renovations by the housing bureau, and private renovations. The distribution of these projects were mainly gathered in Yangmeizhu Xiejie, Taner Hutong, Tiaozhou Hutong, and Cha’er Hutong. The first type was the most known in recent years that won many international prizes. As there were not too much of them, I visited most of the pilot projects to examine their achievements. Some star projects such as Courtyard House Plugin will be selected as the representation for deep evaluation and compared with the other two types. The projects held by the housing bureau were visited just through random passing during aimless wandering. Most of them were in construction process that provided a good chance to witness their building techniques from demolition to reconstruction, or refurbishment, with a frequent visit every two to three days. Private renovations were entirely depending on lucks that I only met one in Nanluoguxiang area, but still has great value for this study. All these projects were marked in the research map and will be compared later for post-renewal evaluation. The evaluation criteria are as following that will be rated respectively:

Increase of living space

Protection of original structure

Thermal insulation properties

Moisture-proof properties

Infrastructure

Cost of money

Cost of time

Feasibility

Community life

The rating will be assessed by means of my own observations and data of comprehensive interviews with local residents and workers, organizers and designers, and third party professionals. The local residents’ opinions and feedbacks will be weighed at the first priority as they were the direct audiences. No questionnaire was accompanied with the interview because private deep conversation is able to gain the most information. The interview questions regarded the local residents’the attitudes toward renewal, such as the participation process, promotion of the living spaces, costs, economic affordability, benefits, positive and negative influences, future expectations, etc. If the original residents were not present when the building was in construction process, their neighbours or workers’ views were also valued. In order to test if the outcome has fulfilled the original intention, the Dashilar Company and architects for the pilot projects were interviewed. They were representing the leaders and organizers’ views upon these renewal projects that determined the level of works that could be done, so their self-assessment will also be an important part of the evaluation. Finally, some non-stakeholders of third party professionals, experts and researchers were also interviewed, their opinions usually were more objective but lacks depth in understanding, which could be very useful complementary resources. In addition, some official organizations were also interviewed to obtaindisclosed policy of population redistribution and basic data, but in fact the available information was very limited. Based on above trilateral feedbacks and opinions, I will conclude with my own views to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of three different renovation models in Dashilar area.

Besides Dashilar area, I also spent several days in other previous renewed areas like Nanluoguxiang and Ju’er Hutong that contributed significantlyto the research findings. For the purpose of realizing the differences of the renewal strategies used in Dashilar and other areas, this part could provide a sharp comparison. Some excellent projects were recommended by the local residents, and these projects could offer useful experiences to make up the drawbacks of Dashilar. Also, some of the unsuccessful experiences could be the warning bell to Dashilar. With a comprehensive review of these renewal practices I hope to present feasible plana for future practices.

Difficulties encountered during field trip included the non-cooperation of essential residents or organizations that resulted in failure to collect certain crucial information. However, the possible outcome could still be analysed, though possibly not entirely accurate. The cultural landscape of the inside of courtyard houses were also not abundant because the tenancy was complicated and break in without authorization was impolite, but I did get very few invitations.

Literature Review on Past Experiences in China

Here several examples are listed and discussed regarding different urban renewal, urban revitalization, and urban redevelopment both in China and abroad. Only by relying on these past cases can we get comprehensive understanding on current practices on similar topics. Through the successful experiences and their deficiencies, we could learn useful lessons in problem finding, renewal policy, renewal implementation, and evaluation system. Their comprehensive methodologies in surveys and data collection can also provide helpful directions on my study. So on the following cases I summarized the core concept or spotlight on practical or theoretical aspects and lessons could be learned from them.

Ju’er Hutong Project

The Ju’er Hutong Project acts as a milestone of the renewal of traditional Chinese neighbourhoods that provided clear directions for later practices that cannot be avoided on such study. The opportunity of such a pilot experiment came from the launch of a test on a small scale, various approaches to renewing dilapidated neighbourhoods by the Beijing Municipal Government Housing Reform Office. Based on the Property Management Bureau’s surveys of housing in particularly bad condition, each of the four districts that composed the Old City nominated a site for renewal. Ju’er Hutong was selected by the East City District as the pilot site. It is located northeast of the Forbidden City, 600 metres east of the Drum Tower, and still contains many especially large and fine examples of old courtyard mansion compounds and gardens, but many of which were neglected or damaged during the Cultural Revolution. As referred to Wu Liangyong, the observations, principles, and methods of rehabilitation are based on following aspects:

rediscovering the urban fabric of the Old City;

establishing a new courtyard house prototype characterized by a series of courtyards with a system of internal access inspired by the “back alley” or “middle corridor” of the typical vernacular housingclusters in Suzhou;

working out a standard courtyard house unit that achieves an ideal balance of sunshine, ventilation, lighting, and other environmental conditions on the one hand, and an intense use of land (floor-area ratio, or FAR) on the other;

developing an alley-like system of access between courtyard units that recalls the age-old system of courtyards and hutong.

The site selection could be traced from 1987, in which a survey was conducted by the planning team under the direction of Prof. WU Liangyong of twenty-four households in the courtyard compound of Ju’er Hutong. The survey included residents’ opinions, living habits, and potential post-renewal needs as well as the housing’s physical condition. Finally, the survey revealed six serious problems that were typical in the old neighbourhoods: threat from structural failure, frequent flooding, roof leakage, lack of light, poor ventilation, and overcrowding. Generally, the residents were living in extremely poor conditions that did not have adequate community facilities. There was only one water tap shared, and a shared public toilet was located about 100 metres away from the courtyard. Many buildings were either structurally hazardous, flooded, or leaking. Moreover, these problems were to some extent triggered by extreme overcrowding, as the population increase over the years forced the residents to build extensions into the courtyards. What’s more, Ju’er Hutong neighbourhood was located at the edge of the Nan Luogu Xiang Traditional Courtyard Housing Preservation District, which meant that the derelict housing could not be replaced by conventional five- or six-storey apartment blocks. Most importantly, the residents were eager to improve their housing and environmental conditions, and they absolutely supported rehabilitation.

The results proved that none of the residents living in the courtyard houses in Ju’er Hutong was happy with the conditions. The urge to renovate their houses and the desire to have more private and adequate facilities is strong. Not only were the housing conditions poor, the neighbourhood relationships were also intense. The residents had to share the limited common space. Naturally, the close relationships came at the expense of privacy and that sometimes led to the occurrence of quarrels. It is also important to point out that, unlike the residents of slums in many developing countries, most of the residents in these neighbourhoods have regular jobs and reliable incomes. As a result, they have to meet their increasing housing needs through adding extensions onto existing houses. Such self-help projects increase residents’ attachment to the area where they live. They seek to improve their physical surroundings rather than to move out.

Whereas the first survey proved that rehabilitation is necessary and imperative, a second wider survey was conducted of the surrounding 8.2-hectare block, investigating issues such as land use, road systems, building quality, and grouping of building clusters. This provided an overview on which the later planning and design decisions for all the phases were based. The second survey went into depth on exploring the same problems and concluded in five aspects:

1) The community facilities could be accessible within close walking distance to Ju’er Hutong neighbourhood, but the neighbourhood lacks open space and social services such as day centres for the elderly, kindergartens, and playgrounds;

2) Except for a few protected historic houses and modern multi-storey apartment buildings, nearly all of the single-storey houses were hemmed in by a maze of temporary shelters recently built by residents. This made maintenance very difficult and hastened the deterioration of the environment;

3) Land use was mixed within the neighbourhood and there was no overall planning, especially the lack of a rational separation between certain industrial and residential uses created pollution and intrusion on the residential living environment.;

4) Street provision was inadequate and the network of lanes was circuitous and carried a mixture of cars, bicycles, trucks, and pedestrians;

5) The infrastructure in the neighbourhood, including water supply, sewerage, power supply, and telecommunications, was obsolete and inadequate.

Finally the Ju’er Hutong project was implemented upon these concerns and has proceeded four phases of planning and construction. In 1992, a post-occupancy survey was conducted among the original residents in order to obtain input for future planning and design projects after five years they were first surveyed. The post-construction, post-occupancy evaluation aimed to determine the extent to which the problems mentioned in the first survey were resolved. With these goals in mind, the planning team at Tsinghua University interviewed thirty-one households in the new housing development. The survey work consisted of face-to-face interviews (conducted according to a questionnaire) and the observation both of interior space and exterior space and the use to which each was put. The conclusion was favourable in general, but some problems were also noted. The evaluation system concerns questions in neighbouhliness, sense of security, and sense of territory and privacy, totally data regarding 17 evaluation questions was collected. From the result it proved the Ju’er Hutong project not only significantly promoted the physical living conditions, but also achieved some cultural and social meanings. The intense neighbourhood relationships were to some extent relaxed, more residents felt they had “reached home” when they entered the courtyard cluster than their own apartments.

But some problems showed during the relocation of the original residents. The Housing Reform policy required that all residents who returned to the neighbourhood after renewal had to purchase their units. This meant that many residents either could not afford to return or, for other reasons, chose a less expensive alternative. Some new residents who could afford it came from other places purchased or exchanged the renewed houses in Ju’er Hutong and changed the original residents structure. The relocation problems was not very severe in this case because there was a government subsidy, but in some other renewal projects the relocated residents have to suffer from a lack of resettlement options and the great distances that relocated residents have had to move.

Although the successful experience was inspiring in the whole nation, but this model has been criticized for being too expensive to be applied broadly throughout the Old City. The primary goal of the Ju’er Hutong experiment was to explore a new courtyard-type housing form. The result of the first phase of the project proved satisfactory; however, the issue of costs was hard to be dealt with. And the great efforts devoted into this experiment were from the supporting of many prestige experts, whom are not realistic to gather again without the unity of central government. A standardized and systematically designed way to reduce cost should be created to control the budget in the future. In conclusion, Ju’er Hutong project achieved a high level accomplishment in old city renewal that provided rich experiences for future practices, but the remaining problems at residents’ relocation and high expenses still waiting to be resolved by later studies.

Nanluoguxiang Renewal

Situated in Jiaodaokou street, Dongcheng district, Nanluoguxiang is an old hutong with a history of more than 700 years sit north of the Forbidden City and below the second ring road. It is famous for its concentration of traditional dwellings known as courtyard houses. The street layout is one of the longest surviving imperial street layouts in Beijing, together with cluster of courtyard houses make it a typical representative of the old city pattern of Beijing. Instead of wholesale demolition and reconstruction, Nanluoguxiang has been renewed with diverse and organic upgrading modes. With the effects of the recent renewal strategies, Nanluoguxiang becomes one of the most attractive tourist center in Beijing with thousands of people visiting every day. Dazzling trendy stuff and traditional courtyard houses shows a collision of modern and tradition, which makes it the most special hutong in Beijing.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, a number of administrative institutions set up their offices in Nanluoguxiang, leading to the demolition of some traditional courtyard houses, temples and so on. Many of these courtyards were expropriated by major government institutions in order to be used as residential quarters for their key officials and their family members, and more houses were confiscated during the Cultural Revolution to be transformed into public rental dwellings. Over the years, they had gone through informal extension to existing structures and subdivision to provide additional dwelling space, destroying most of their original characteristics (Zhang, 1997).

In 2002, the Beijing municipal government earmarked 25 conservation areas in the Old City of Beijing, in which Nanluoguxiang was selected in. By the time the conservation plan of Nanluoguxiang was announced, its land coverage reached 83.8 hectare, accommodating around 22,000 registered residents with the resulting population density of 262 people per hectare (Beijing Municipal City Planning Commission, 2002, p. 158). The average housing space is only 6.9 square metres (Jiaodaokou Street Office, 2007). In order to ease the housing pressure, the plan aims at decreasing the population density to 167 people per hectare by reducing the population from 22,000 to less than 14,000. So a large amount of local residents had to be permanently displaced. The previous large-scale demolition and reconstruction were banned in these areas and replaced with “micro-circulation” strategy.

According to Shin, the key planning guidelines were as follows:

1. preservation of the overall style and features of conservation areas;

2. preservation of authentic historical features and heritage;

3. incremental renovation;

4. improvement of environmental quality and infrastructure as well as residents’ living standard;

5. encouragement of public participation in conservation works

After the plan was disclosed, before the government began to implement any substantial actions, some individual pioneering entrepreneurs smelled the business potentials and took actions immediately. Many trendy shops including small bars, cafe, tailor-made boutiques and so on were sprouting very quickly. In a short time, the central main lane of Nanluoguxiang was fully occupied, and gradually turned into a culture-led consumption space that attracts a large flow of tourists. The historic and tranquil atmosphere was the decisive element that made it different with other commercial areas and also the most characteristic that brought more potentials for future developments. As a result, the housing prices have increased a lot that led to a selective process of businesses and living, which brought the problem of gentrification. In order to appear on the private rental market, refurbishment and facelift was applied to the courtyard houses, eventually consumed by those who sought trendy living in historic quarters. (Shin, H. B, 2010) The main renovation activities in Nanluoguxiang were propelled by these private investments. But such renovations were more likely to be prevalent among those few residents whose house faced hutong, whilea greater number of residents who were “under the iceberg”, living in the deep courtyard houses, could not benefit a lot. Apparently, most of the houses were renovated for commercial use but not for dwelling. Other residents even suffered from the inconvenience brought by the commercial activities that were not relevant to them.

Besides private renovation, the local state then released a goal of creating “Nanluoguxiang Culture and Leisure Street”. A wide range of public works were carried out, including the demolition of illegal structures, relocation of offices such as police station, pavement of the central lane and infrastructure upgrading. Face-lifting was the key to neighbourhood beautification. Walls were repainted in grey to provide a uniform and pseudo-ancient look, and very often, an additional layer of brick was applied in order to hide dilapidated façade.(Shin, H. B, 2010) The main renovation activities in Nanluoguxiang were propelled by these private investments. But such renovations were more likely to be prevalent among those few residents whose house faced hutong, whilea greater number of residents who were “under the iceberg”, living in the deep courtyard houses, could not benefit a lot. Apparently, most of the houses were renovated for commercial use but not for dwelling. Other residents even suffered from the inconvenience brought by the commercial activities that were not relevant to them.

Besides private renovation, the local state then released a goal of creating “Nanluoguxiang Culture and Leisure Street”. A wide range of public works were carried out, including the demolition of illegal structures, relocation of offices such as police station, pavement of the central lane and infrastructure upgrading. Face-lifting was the key to neighbourhood beautification. Walls were repainted in grey to provide a uniform and pseudo-ancient look, and very often, an additional layer of brick was applied in order to hide dilapidated facade. (Shin, H. B, 2010) Especially the Olympic Games in 2008 boosted a wide range of such activities. Since it also did not generate any benefits, the government could not afford a long-term, large-area investment, so it was not sustainable. In addition, these renovations were mainly focused the frontages in main hutongs. If you walk into a courtyard house, you would see the inside courtyard and houses were still in a bad condition. If their houses were not facing hutong or located too deep, the area conservation would not have any influence on their families. These face-lifting and beautification activities were just to make Nanluoguxiang presentable to visitors and attractive to businesses, but they did not have any effective improvement of local residents living conditions.

From 2008, the local housing bureau has been carrying out selective demolition and reconstruction of dilapidated rental courtyard houses owned by them, which posed serious health and safety threats. Those projects were funded by the municipal government; the local residents did not need to pay anything. They did improve a little of the physical living environment, but the reconstruction could not increase the dwelling space for re-housing, which was the real concern of local residents. The living condition was still crowded. Although the reconstruction of courtyard houses used the traditional way of construction, but the houses were not the original houses anymore— their souls and historical values have been lost. It is well known that restoring the old as the old is the best way to prolong its life, but the cost of money and time would be also great, so the housing bureau chose a cheaper and simpler way to demolish and reconstruct, because they could not afford such money and time. They were seemingly improving the living condition one house by one house, actually they were causing damages to the historical courtyard houses. No matter how similar the reconstructed house is to original one, we cannot guarantee they would be 100% the same. In this way, not a long time later the whole area would be all reconstructed again, by that time regret would be too late.

The efforts of opportunistic investors and local government jointly triggered the displacement of original residents and loss of community life. In order to achieve the goal of reducing population density, a model called “micro-circulation” was applied to the restoration of the courtyard houses in Nanluoguxiang by the local authorities. This policy required the local residents to move out of the original houses with some compensations, and the emptied courtyard houses could be released for restoration by corporate and individual investors, which reduced the financial burden of local authorities.

In contrast to the commercial renovation and government renovation, some privately-owned courtyard houses have been restored to their original features the best, with the most traditional craftsmanship and technologies. The careful maintenance can be attributed to the sense of belonging that people usually cherish their own things rather than the public. However, private renovation had to be carried out in their own expenses, and the exquisite craftsmanship was also more expensive than cheap face-lifting ways. Due to the history of confiscation, welfare housing allocation and housing reform during the last few decades, Beijing’s courtyard houses tend to experience fragmented property rights, and the public rental tenure has been the dominant tenure form in historic quarters while private homeownership is marginal. (Shin, H. B, 2010) There were only a few courtyard houses owned by private owners. This kind of renovation was not realistic to be applied to a large area.

In conclusion, the glamourous look of Nanluoguxiang has attracted great attention from large amount of business investment and tourists. Howevr, behind the appearances the living conditions of the local residents are still worrying, which is often neglected. The most characteristic element of the renewal of Nanluoguxiang was the injected capital that did improve the vitality and popularity in Nanluoguxiang, but it also caused the loss of original community life. The local government had some attempts, but as they did not have strong financial resources as backup and that they could not make benefits, these tries were just floating on a superficial level, and did not improve the living conditions. The displacement also aggravated the loss of community spirit. Physical upgrading has overweighed the residents’ social lives. Only the private renovation showed some good effects, but the ownership issues left over by history could not be resolved in a short time. The experiences of Nanluoguxiang have been regarded as a success and applied to other areas, yet we could not say we have found a good way to renew the old city of Beijing, the future exploration still has many works to do.

Chapter 2

The Old Cities of Beijing and Dashilar

Historic Urban Pattern of Beijing

Beijing, well known as China’s capital, has a more than 3000 years’ history and has served as the capital of China for the past eight centuries. Beijing has the essence of an artificially planned city, where its unique cultural values are reflected in its traditional layout and historic patterns. The prosperity of Beijing began in the Liao Dynasty, where for the first time it became the subcapital. Then again and again it was destroyed, rebuilt, and modified until now. The modern Beijing was developed from the core center of Ming and Qing Dynasty’s layout and expanded to today’s five ring roads. The original shape of the Old City of Beijing can still be recognized as the second ring road on the map.

Fig. The ring roads layout of Beijing. (drawn by the author).

In 936, Liao-Nanjing, on the site of modern Beijing, was established as the most southerly of 5 Liao dynasty subcapitals. In 1153, under the name of Jin-Zhongdu, Beijing rose to become the most prominent capital of the Jin Dynasty. In 1267, Kublai Khan ordered the transfer of the Yuan dynasty’s capital from Mongolia to a site located northeast of the destroyed ruins of Jin-Zhongdu, naming it Dadu. Dadu is regarded as the precursor of present-day Beijing. After the fall of the Yuan dynasty, in 1368, Dadu-Beijing temporarily lost its capital status, when the new Ming emperor moved the capital to Nanjing. The third Ming emperor, Zhu Di, decided to reinstate the Dadu site as the Ming capital, building a new capital there under the name of BEIJING in 1421. In 1644, the first emperor of the Qing dynasty, Shun Zhi, decided to retain the capital in Beijing. Apart from a brief period during the civil war, Beijing has remained as the capital ever since (Hou, 2000).

Fig. The plans of different dynasties of Beijing. (drawn by the author).

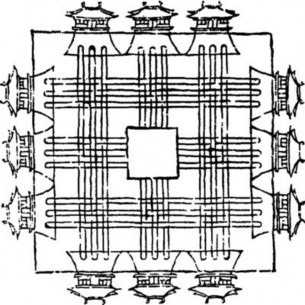

The historic context of the Old City of Beijing shows a rigid grid street system that complies with north-south and east-west axes. This distinct urban fabric evolved from traditional Chinese planning theory that was traced back to the book Zhou Li (Chun Qiu period, BC770-

BC476): “nine vertical axis, nine horizontal axis”; “palaces in the front, markets in the rear”; “left ancestral worship, right god worship” and had remained intact until recent years.

Fig. Planning priciples in Zhou Li. (Retrieved

from www.duguoxue.com)

These principles and the historic pattern of hutongs and courtyard houses in a grid system were laid down in Yuan Dynasty. During the start of the Ming Dynasty, the Yuan central palace was destructed because of a tradition that the new dynasties build their own palaces and temples and demolish the old, which on the nearby site erected the present Forbidden City. However, the walled city that surrounds the Forbidden City was inherited by Ming and its perimeter was modified for easier defense. After the takeover of Qing Dynasty, the walled city was fortunately inherited again, and later on an Outer City was proposed in 1476 and built in 1553 to surround the original city for the sake of future expansion and fortified defense. Due to insufficient funds and continuous wars, however, only the southern part of the Outer City was built. Since then the “凸” shaped Old City of Beijing appeared and lasted until now. The Qing Dynasty inherited almost all the institutional practices of its predecessor, the Ming, and made few changes to the capital city, thus ensuring its preservation until the 1950s.

Outer City is the place where the research area of Dashilar sits. Differing from the Inner City, the Outer City is a more vigorous, chaotic and mixed-culture area. In 1648, the Qing emperor Shun Zhi settled his compatriots, the Manchus, in the quarters surrounding his palace. Mongols were located in adjacent zones in the Inner City and Han Chinese in the Outer City. Because Han Chinese were in lower class in Qing Dynasty, the Outer City (Chinese City) usually was seen as the poor and loosely regulated area in contrast to the rich and aristocratic families’ Inner City (Tartar City).

Without elaborate planning, the Outer City was not laid out along a grid pattern, so there are many crooked streets and narrow alleys. Buildings are a much smaller scale than in the Inner City. The Outer City has traditionally been a commercial area. Closer to the Inner City, the areas were more prosperous and built in higher concentration. Traders from China’s provinces tended to form their own neighborhoods, each drawing architectural inspiration from their respective native region. New immigrants would also first settle here and make a living, thus bring more commercial activities.

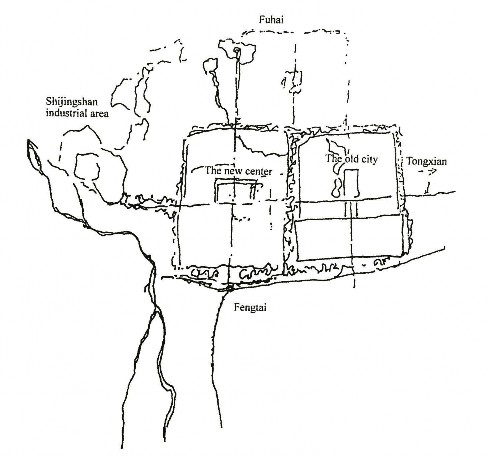

Fig. The formation process of the Old City of Beijing. (drawn by the author)

The Old City is divided into twenty-nine square city blocks measuring 750 meters on each side (55 hectares). Such mega-blocks are surrounded by main commercial streets where convenient shopping and public transport systems are located (He, 1990). The blocks are subdivided into long, narrow residential quarters by lanes called hutong 3, which run from east to west, 80 to 100 meters apart. Such lanes are mainly used by pedestrians and bicycles, and most of them are unsuitable for motor vehicles (fig. 3.3) (He, 1990). This kind of layout not only affords residents easy access to transport and shopping centers, but keeps noisy traffic away from the residential areas (Broudehoux, 1994).

Professor Wu Liangyong of Qinghua University, who doubles as academician of both the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering, commented:

Urban construction in ancient China is characterized by an integration of urban planning with urban designing, architectural designing with gardening. This is globally unique. No precedence is found among the best-designed ancient cities in both the East and West, and old Beijing definitely stands out as the best among them. It is indeed no exaggeration to describe old Beijing as the best example, the “gem,” of ancient city planning across the world.

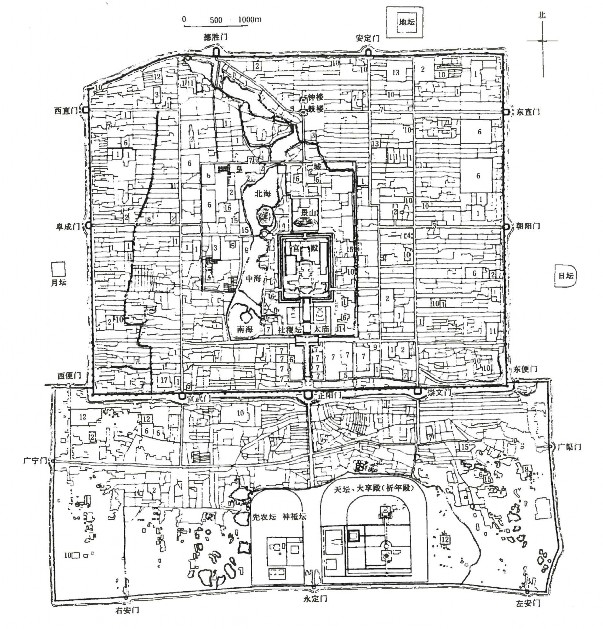

Fig. Map of the Old City of Beijing. (Wu, 1999)

Beijing’s urban pattern and architectural features are remarkable and unique. Ever since Marco Polo’s visit to China, Beijing has been the object of high praise from planners around the world. The renowned Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen, in his book Towns and Buildings (1951; v), states his admiration for Beijing in these words: “…[T]he entire city is one of the wonders of the World, in its symmetry and clarity a unique monument, the culmination of a great civilization.” Similarly, the American city planner Edmund Bacon (1980; 244) describes the old city of Beijing as “possibly the greatest single work of man on the face of the earth” (Broudehoux, 1994).

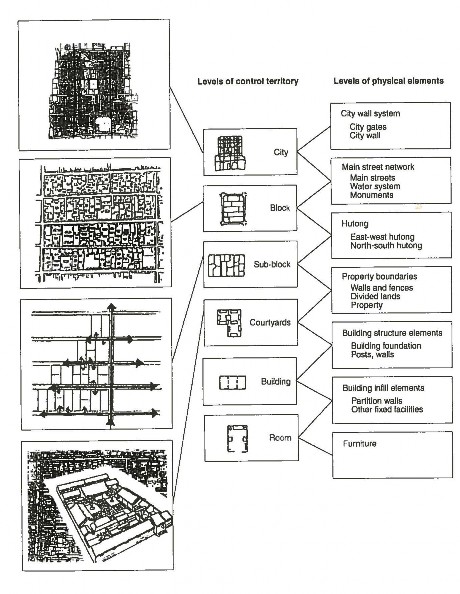

According to Wu’s summary, the urban fabric and hierarchy of old Beijing could be sorted out in following order from large scale to small scale:

1. The City.

2. The Street Block.

3. The Neighbourhood.

4. The Hutong.

5. The Courtyard Compound.

6. The Building.

7. The Room.

Fig. The hierarchy of urban spaces of the Old City of Beijing. (Wu, 1999)

Hutongs

Hutong is a kind of narrow lane that composes the traditional urban fabric pattern of the Old City of Beijing. It first appeared as a Mongolian word in Yuan Dynasty that refers to the space between tents or the way to the well. Yuan dynasty city plans show three types of street: big streets (around 37.2 m wide), small streets (18.6 m wide) and Hutongs (9.3 m wide). Big streets and small streets mostly ran North-South, while the Hutong lanes, mostly ran East-West. So, Hutong lanes act as the smallest unit of the traffic system that connects adjacent square blocks of lines of courtyard houses, which provide shelter from the wind and give a strong sense of privacy. Hutongs are also the traditional neighbourhood unit to organize daily activities. Nearly all the courtyard houses have their main gates facing hutongs. Indeed, this network of arteries provides the soul of the real city and typically hutong residents consider themselves as true Beijingers, with many speaking their own hutong dialect (Tibet Heritage Fund, 2004).

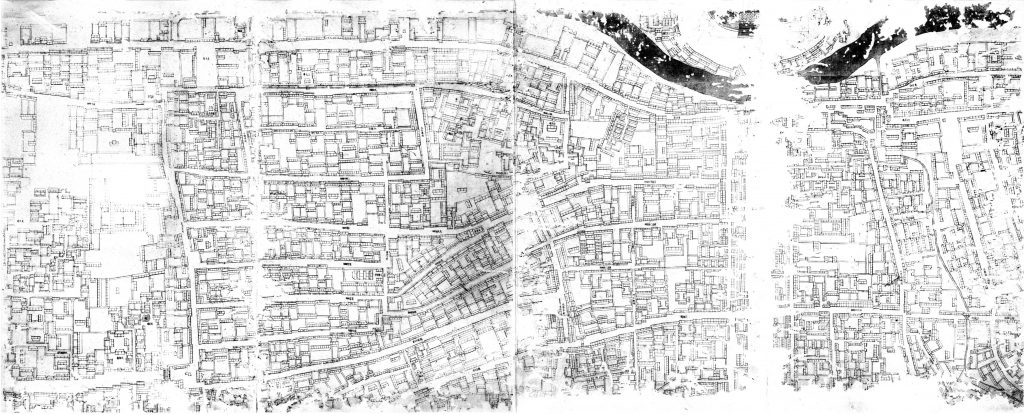

Fig. Hutongs and courtyard houses show on the Qianlong map. (Modified by the author with resource

from dsr.nii.ac.jp)

The Tibet Heritage Fund (2006) found that ‘…the majority of residents actually praise the life-quality of hutong in terms of social relations with their neighbours (developed over decades of having to live together in small spaces), security, greenness, quietness and, of course, the convenient location in the centre of Beijing’.

Traditional Courtyard Houses

Siheyuan, the best known courtyard house type in Beijing, composes the basic unit of hutong and makes up most of the central part of the city. Representing the traditional Chinese culture, the courtyard houses have been used for several thousand years. The ancient Chinese favored this housing form because enclosing walls helped maximize household privacy and protection from wind, noise, dust, and other threats. The courtyard offered light, air, and views, as well as acting as a family activity space when weather permitted (Zhang, 2016). It also reflects the eastern introverted personality that organizes daily activities inside the walls with close family members.

Fig. Comparisons of different couryard concepts. (drawn by the author with reference of Lu, X. 1996)

Normally the layout of a courtyard house has four-side houses positioned along the North-South and East-West axes. The rooms on different sides indicate a clear family hierarchy of that person’s position and seniority. The building positioned to the North and facing the South is considered as the main house (Zheng Fang), which is dominant in a courtyard house that comes with the best orientation to capture the most sunlight. It is reserved for the head of the family or the oldest generation in the family. The buildings on East and West are side houses (Xiang Fang) that rank second in the hierarchy, and are used to accommodate the younger generations and their families or other relatives. The opposite house (Dao Zuo Fang), located on the southernmost edge of the courtyard house, is a North-facing building that is kept low to allow sunlight into the courtyard resulting in the smallest and darkest room. It is usually used by servants or as service spaces where the family would gather to relax, eat or study. A separate backside building (Hou Zhao Fang) sits behind the northern building is usually for the unmarried daughters and female servants, who are seen as improper to be directly exposed to the public.

Fig. Use of courtyard house. (drawn by the author with reference of Lu, 1996)

The courtyard is accessed through a main gate at the southern end, and often there is a back door on the northern side. Behind the gate, normally there is a screen-wall (Ying Bi) inside so that outsiders cannot see directly into the courtyard and to protect the house from evil spirits. Outside the gate of some large courtyard houses, it is common to find a pair of stone lions. The gates are usually painted vermilion and have large copper door rings. All the rooms around the courtyard have large windows facing onto the yard and small windows high up on the back wall facing out onto the street. Some do not even have back windows (Chinadaily, 2004).

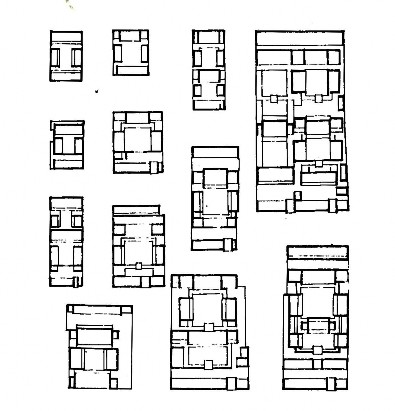

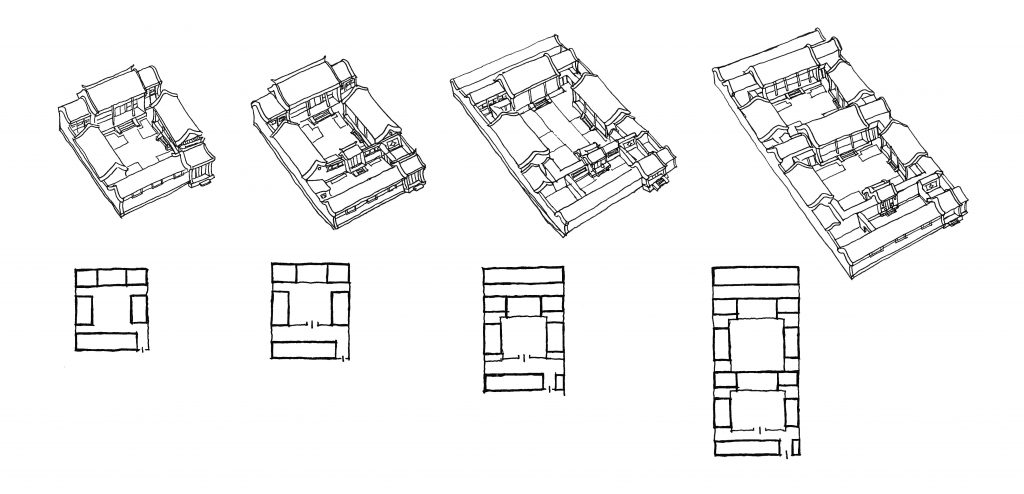

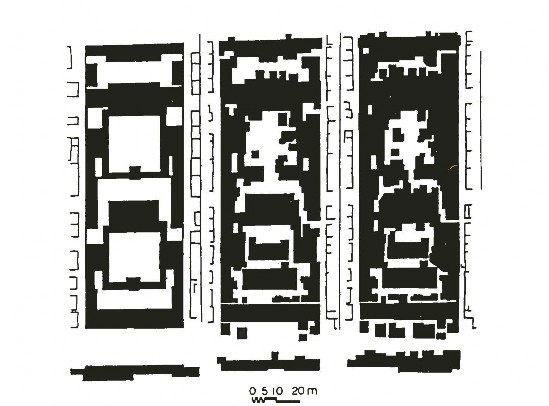

The layouts of courtyard houses are variable based on the single-courtyard prototype. Generally, a single-courtyard house is for an ordinary family, but there are also multi-courtyard houses that could accommodate several subfamilies with a serial courtyard combination. Although, no two courtyard houses are exactly the same, especially considering that adjacent courtyards could be arranged on a longitudinal axis or double axes of both longitude and latitude. Representing a mark of prosperity in ancient times, these large compounds often have more complex usages as houses. Thus, the head of the family would move to the deepest courtyard because residing deeper indicates greater prominence. The first courtyard is used for reception, kitchen and servants.

A major attraction of the courtyard house is its secluded and peaceful atmosphere, affording a degree of privacy and calm within the city’s bustle. The ambience of the courtyard house is closely tied to the traditional lifestyle of China’s urban families (Tibet Heritage Fund, 2004).

Fig. Different combinations of courtyards. (Lu, 1996)

The historic pattern of Dashilar

Located just south of Tiananmen Square, west of Qianmen Street, immediately outside of the core area of the Old City of Beijing, Dashilar has been one of the most prosperous cultural areas in Beijing for 600 years. The unique position for its proximity to the Inner City made it the most important spot in the Outer City that developed hundreds of commercial and cultural activities, including some of country’s oldest shops, theatres, and famous celebrities. As mentioned before, during Qing Dynasty the Han Chinese could only reside in the Outer City, and the entertaining activities were only allowed outside of the Inner City. New immigrants’ first stop was also in Dashilar, and many of them were making a living by acting or retailing, which created the concentrated commercial atmosphere and mixed land uses.

Dashilar is a traditional commercial area with traditional traders in old scrolls, calligraphy, paintings, tea, and traditional medicine. Since the early years of Ming dynasty, it has been the centre for commerce, services, entertainment and handicrafts in the City. The area is thus the home for major Chinese traditional brands such as Tong Ren Tang (medicine), Rui Fu Xiang (silk) and Bu Ying Zu (shoes). Altogether 104 assembly halls (huiguan) including regional resthouses and 61 temples are to be found in the Dashilan Area. During various periods theatres were prohibited to open in Beijing City centre and Dashilan became the centre for tea gardens, theatres and cinemas. In 1900, brothels were ordered to move outside the inner city and eight famous lanes were developed in the Dashilan area (McIlveen & Bro, 2005).

Fig. Location of Dashilar area. (drawn by the author)

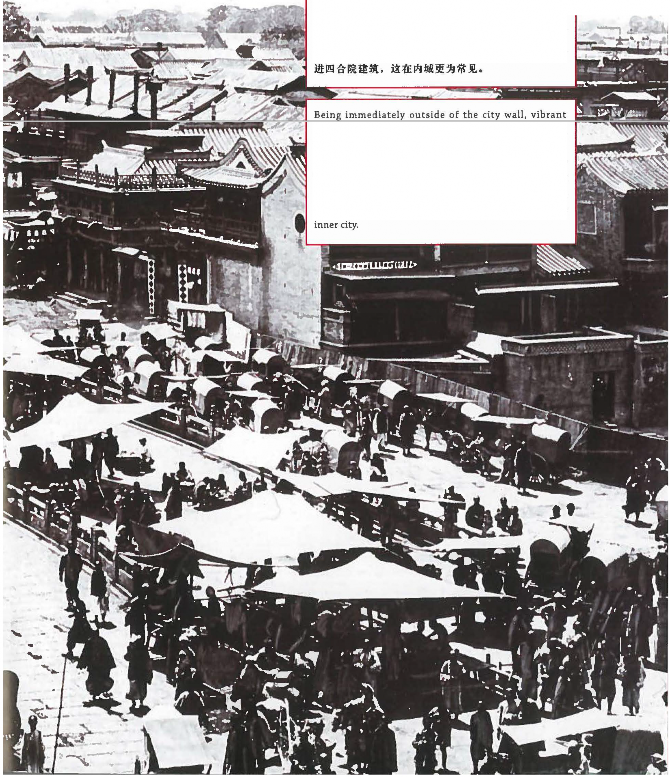

Fig. Bustling old scenes of Dashilar area. (Dashilar Investment Ltd)

In Ming Dynasty, the name “Dashilar” did not exist, but instead was called “Langfang Sitiao.” In 1488, in order to secure the public safety of the capital, the central government built wooden fences at all the entrances to the streets and lanes in Beijing. Gradually with the increase of fences until Qing Dynasty, these fences were extremely large and thus got the name “Dashilar.” With the passage of time, “Dashilar” gradually became the formal name of the street replacing “Langfang Sitiao.”

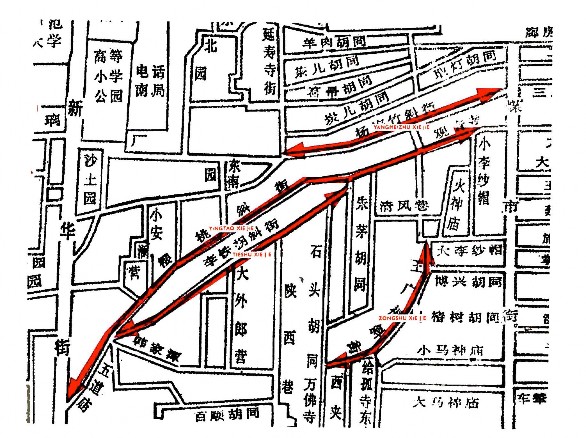

Dashilar covers an area of approximately 1.2 square kilometres in a quadratic shape. It is surrounded by Qianmen Street, Qianmen West Street, Nanxinhua Street, and Zhushikou Street, since Beijing was planned on a strict grid system running north-south and east-west with the traditional planning principles in Zhou Li, especially inside the Inner City. Thus the diagonal street pattern in the centre of the Dashilar area leading from the historic areas southwest of the Ming Dynasty City towards the previously existing bridge crossing the old moat and the southern Main Gate is unique in Beijing and breaks away from the traditional chess board pattern inside the city wall (McIlveen & Bro, 2003). Oblique Streets, or Xie Jie are a defining aspect of Dashilar’s urban fabric. There are four iconic oblique streets named Yangmeizhu Xiejie, Yingtao Xiejie, Tieshu Xiejie, and Zongshu Xiejie crossing the central part of the area, marking a vibrant and self-organized development in the ancient time.

Fig. Historical map of Dashilar area. (Dashilar Investment Ltd)

Other than the unique street pattern, Dashilar is one of the last coherent ancient and traditional hutong and courtyard house areas in Beijing and it is of paramount importance that it is preserved and protected in its natural state as a living, vibrant but also viable urban environment. For 600 years’ existence, the hutongs and courtyard houses are the most important testimony to this long history. The courtyards are, however, smaller in the Dashilar area than those originally found inside the walls of the Inner City as primarily lower ranking government officials, traders and merchants were residing here. At the same time, the courtyard houses are also lined in a more irregular pattern with the squeezing of irregular shaped hutongs.

Referring to McIlveen and Bro’s report in 2005, there appear to be several most important characteristics the Dashilar area that indicate its uniqueness:

Fig. Street pattern of Dashilar area. (drawn by the author)

• The unique urban fabric and the diagonal street structure

• The area’s important role in history in terms of both function and cultural melting pot

• The original hutongs and courtyard houses of which some have been inhabited by people of importance for the development of China

• The cradle of the Peking Opera

• The ancient traditional commerce with century old brands

• The linkages between the Forbidden City, Beihai Park, the Temple of Heaven, The Tiananmen Square and the Dashilan Area along the Ming Dynasty north-south axis

• The location and role of the Dashilan Area as a transition area between the ancient Jin and Yuen Dynasties, the Ming and Qing Dynasties and the City of the 21st Century evolving from the first republic in 1911 to the modern metropolis of today.

• The multifunctional and original built environment with ancient tea houses, rest houses, guild halls, temples, opera scenes, commercial shops, banks and money exchanges

• Period typical individual buildings of architectural interest from the earliest Ming dynasty classic style to 19 and 20ies century hybrid architecture with mixed western and Chinese styles and features

• The traditional culture of those resident families that have been living and working in the area for generations

As a living exemplar of Beijing’s distinct culture and tradition, Dashilar was the capital city’s most prosperous and bustling commercial center. Today, it both preserves and continues in the historical and traditional customs and practices of its heyday. Dashilar is definitely qualified as one of the most important heritage sites in Beijing. With its own special history and distinct pattern, Dashilar is a particular historic area that is worth special attention even among the few remaining traditional areas in Beijing.

Chapter 3

The Current Living Conditions in Dashilar

Current Living Conditions in Dashilar

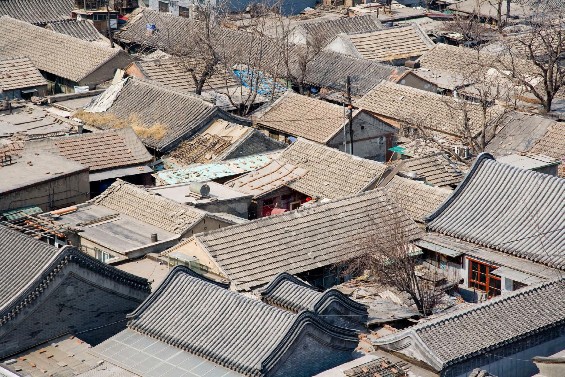

Today’s Dashilar is an area of 1.26 sq km under the management of Xicheng District, including 9 communities, 33 neighbourhood committees, and 114 hutongs. The area has a registered population of 54,150 that makes Dashilar the most heavily populated area in Beijing with close to 43,700 people per square kilometer. The most shocking fact is that the average building height of Dashilar is a one-storey courtyard house. In addition to the number of permanent residents, Dashilar is catering to a large number of visitors and tourists. Many people stay in the area as short-term visitors visiting friends and relatives, and the area also caters to a large number of domestic tourists (McIlveen & Bro, 2005). During the field trip in May in Dashilar, I have found the average living conditions are extremely poor. The entire traditional area was in chaotic and messy conditions; dozens of people were squeezed in small rooms, courtyards had vanished and were infilled with illegal sheds, hutongs were crowded with farfetched sundries, and municipal infrastructure was so lacking that people had to rely on inconvenient sanitary facilities.

The main problems are summarized:

1. Overcrowding living conditions.

Dashilar has a population density two times that of the average population density of the central area of Beijing. In the research area, the data from McIlveen & Bro’s survey is 25 sq m per family. While by my own research resulting from talks with the local residents and local housing officers, the average living space is 12 sq m. On average there are more than ten families sharing one courtyard, which used to only accommodate one family.

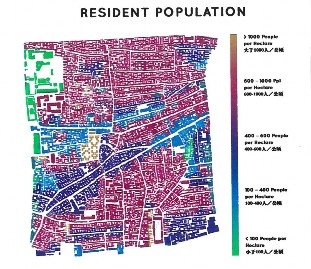

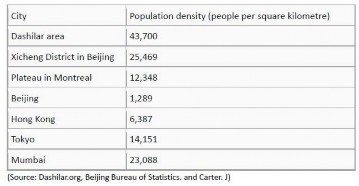

It is apparent that the Dashilar area has an extremely high population density, seeing that the average population density of Beijing is 1,289 people per square kilometer, 25,469 people per square kilometer in the Xicheng District of Beijing, and 12,348 people per square kilometer in the Plateau area in Montreal. However, such a huge population in Dashilar was born by single-storey courtyard houses, from which we can imagine how hard the living conditions would be. What’s more, 17% of the residents are beyond 60 years old, which is 10% higher than the average aging level of China. The group with the most difficulties, such as unemployment and immobility, are making up 30% of the total residents.

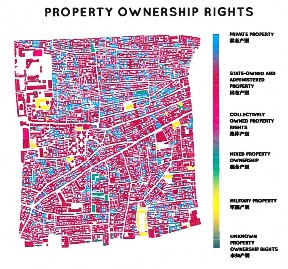

2. Complex housing ownerships.

Due to some historical issues (which will be explained later of this chapter), the housing ownership in Dashilar is very complicated. The most common type is public housing. It originated from the housing policy of Jingzu-House in the 1950s. These buildings were managed, rented, and maintained by the local housing office. New immigrants, or those who could not afford private houses, were placed by the government in these houses since they only needed to pay a low rent. Thus, most of the occupants in the courtyard houses in Dashilar are tenants. Although those tenants have been living in the area for over 30 years, they are still renting the houses and do not own them even today. However, they have the right to live, use, or rent, but not sell.

Nowadays the government still offers an extremely low rent to tenants at around 100 CNY (approx. 20 CAD) per year, which almost free. As most of the tenants are very poor, this protects the residents from market forces, but also has negative effects. There are also private properties, while only a few, and these courtyard houses are also occupied by the “squatters” that date back more than 30 years ago. Generally private housing is in better condition, because the owners intend to maintain their property.

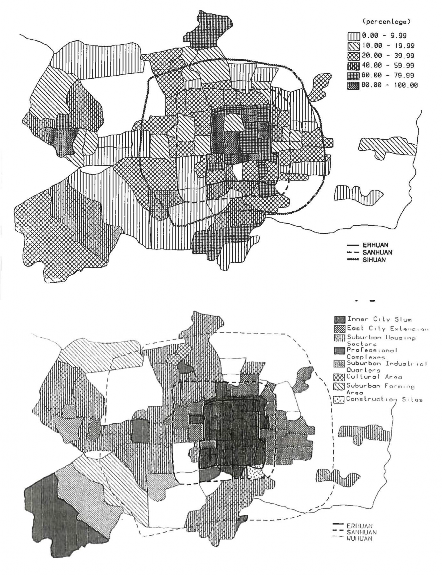

Fig. Left: the distribution of population density. Right: the distribution of ownership rights.

(Dashilar Investment Ltd)

3. Dilapidation and illegal extensions.

Among the 11 communities in the Dashilar area, there are 10 communities filled with courtyard houses, with a total of 33,000 houses and 2950 courtyards, of which 90% are in dangerous conditions (Zhu, 2005). The common problems include roof leaks, rotten timber structures, humidity, and walls can be found anywhere. The piles of sundries and illegal extensions in the courtyards block the sunlight from entering the houses. Overcrowding inside rooms that are filled with living goods spare no room for ventilation or any fresh air. Humidity goes from the bottom of the walls and creeps up to the roofs that leads to the damage of the wood structures.

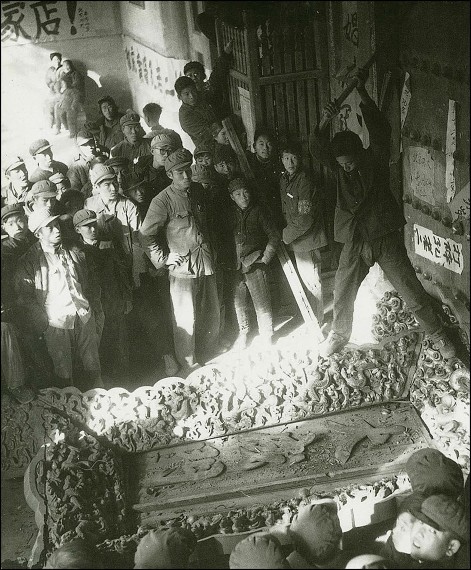

Illegal extensions are common scenes in Dashilar, usually makeshift constructions of bricks with asbestos or tin sheet roofs. Most of the illegal extensions are used as kitchens but a few serve for living. During the social reforms of the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution, courtyards were sub-divided, and in order to accommodate thousands of homeless people after the 1976 Tangshan earthquake, further sub-divisions were made, leading to a sprouting of flimsy extension buildings that fill up most of the courtyards of publicly-owned housing. Residents have also often modified or reconstructed the original buildings (Tibet Fund Heritage, 2005). In order to extend the living space, makeshift constructions in the courtyard houses are very common. Any free space has been used for piecemeal development in the form of infill between buildings. This development, which to a large extent has been uncontrolled and unplanned, viz. illegal in some cases, leads to dangerous fire hazard conditions and a demand for water, electricity and sewerage which surpasses the capacity of infrastructure (McIlveen & Bro, 2005).

The complex ownerships also triggered dilapidation of courtyard houses. Housing in old courtyard buildings was so cheap that it seemed to many residents not to be worth any investment of effort or money in upkeep (especially combined with the insecurity about the length of tenure – most residents are convinced that sooner or later their courtyard will be demolished and they would have to move away). The housing department had no sufficient budget for regular maintenance, either. After 40 years of neglect, many buildings have assumed a run-down appearance, making them easy prey for the Weigai replacement system (Tibet Fund Heritage, 2005).

4. Lack of adequate municipal and sanitary facilities.

The provision of modern services and facilities has not been introduced and the living standard of the Dashilar inhabitants remains the same as fifty years ago. Accessibility and transport has formed a serious problem for the development. The dwelling conditions are very low with congestion of inhabitants in a relatively small living space, with very poor heating and maintenance systems (McIlveen & Bro, 2005).

Households have to share water supply. Usually there is one water tap in one courtyard, shared by several families and up to twenty households. Many families extended waterlines into their homes on their own, normally only to feed the daily need of the kitchen.

Almost none of the local residents have private washrooms, and they have to share the public toilets and public bathhouses. It is very common to find the free public toilets in hutongs everywhere, within a walkable distance of 200 metres. However, these public toilets are in very poor conditions that do not provide closestools and have bad privacy. They are usually not connected to any sewage system, but are emptied regularly via pump trucks. Traditionally, every courtyard had at least one composting toilet, but the system of manure collection became obsolete as tenants, desperate for space, took over most of the toilet spaces for building extensions.

Before 2004, coal heating was the main heating method in Dashilar, but it was very dangerous and had bad environmental effects. Now electric heating is popularized, however, and it is no longer a problem. Yet because there are no gas lines for kitchens, gas tanks are the only current solution but they are also dangerous.

5. Insufficient spaces for daily life.

With the heavy pressure of overpopulation and building extensions, the spaces for daily life activities are in short supply. A large percent of hutong and courtyard spaces are occupied with all kinds of objects that deteriorate the living conditions in Dashilar. The original narrow hutongs were not designed for modern vehicles, while today there are small cars, electric bikes, bikes, and rickshaws parking everywhere that make the hutongs narrower for traffic.

It is common that messy sundries pile in along the hutongs and inside the courtyards. Most of them can be recognized as useless garbage, but the local residents have the habit to collect and keep it. This phenomenon can be attributed to their poor financial situations. Usually poor people intend to collect and store things which may be useful one day, and are not willing to throw them away even if they have not been in use for a long time. In contrast, the rich people can afford to buy anything new that is needed, so they do not like storing the useless stuff. However, this phenomenon deteriorated the already narrow living spaces and made the living conditions more crowded in Dashilar.

In addition, there are some daily activities which demand more space. Normally courtyard houses are not equipped with washing machines nor drying machines. So every sunny day lots of washed clothes, sheets and shoes are hung along the hutongs to air. Traditional Beijingers also like keeping pets. Even in such a crowded situation, they will still spare some space to keep their birds, which are seen as an important component of their daily life.

6. Lack of green spaces.

There is lack of green areas and open space for leisure activities. Most of the activities happen on the hutongs, mixed with bustling bicycles and electric bikes. Hutongs become the fairground for children and also the place of chess for old people. Because hutongs are too narrow, even trees do not have space to grow so the heat island effect is also severe in Dashilar. People have to plant their own little gardens with bonsai.

7. Fire dangers.

Most of the streets are very narrow and cars are not allowed to enter these small streets, so it does not allow fire engines to get to the proper position. There are 75 hutongs of the total 114 hutongs that cannot let fire trucks get in (Zhu, 2005). The hutongs are too narrow. The electricity system is also old and thousands of electrical wires, phone lines and cables crisscross all over the sky of hutongs.

8. Sense of public security is weak.

As a result of the complex residents’ composition of courtyard houses, people living in one courtyard can hardly comply on the working and rest time. Thus courtyard houses have to keep the main gate open 24/7. There are too many temporary and floating residents who are unemployed in this area, which makes the security condition more complex.

Historical Causes of the Current Situation